ISSRC Blog

This blog provides an opportunity for pithy observations or reflections on topical rural crime news and developments, a summary of research, promotion of publications, advertisements for upcoming events… and more! If you would like to contribute, email a submission of no more than 500 words to admin@issrc.net

New Research! Rural Crimes Committed in 1940’s Ireland

Written by Dr Clay Darcy, Technological University Dublin, Ireland.

A recent research article by Clay Darcy, PhD, published in the International Journal of Rural Criminology (Vol. 8, Issue 1) examines a volume of recorded crimes compiled by Irish Police (Gardaí) during the early 1940’s in three small rural villages on the East coast of Ireland. The volume is being analysed as part of an ongoing sociological research project into historical rural crime in Ireland.

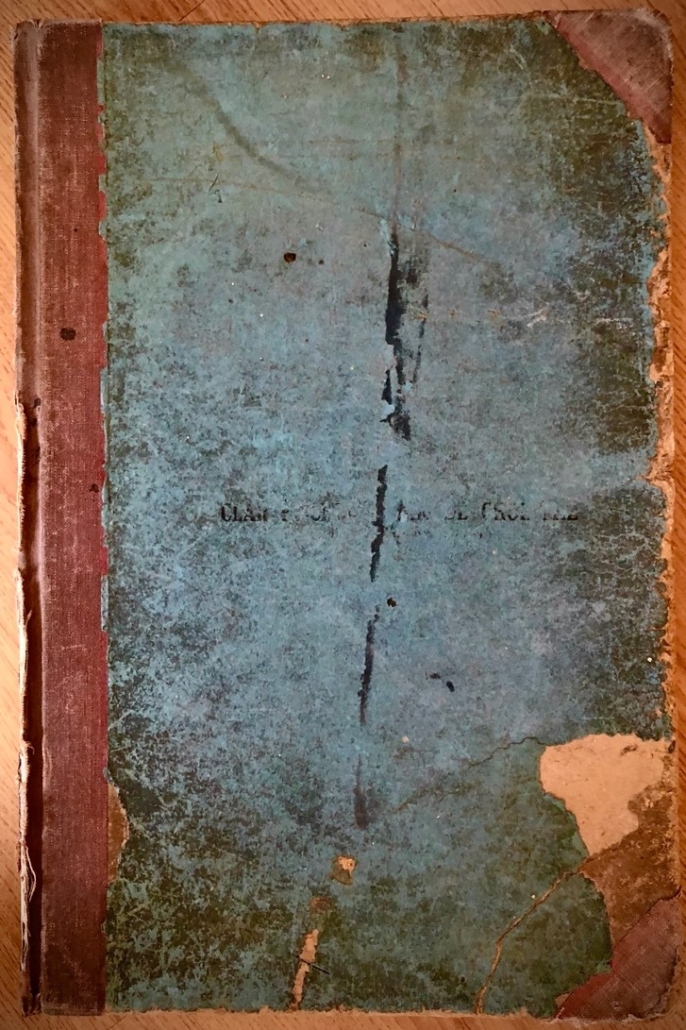

Front Cover of the Volume of Crimes

This article focuses on crimes committed between 1941 and 1943. Darcy uncovers records of various types of crime within the volume, including; indecent assaults, concealment of births, attempted suicide, sacrilege and larceny, among others.

The article provides a historical backdrop to the research, describing what rural Ireland was like in the 1940’s. It was a period known as the ‘State of Emergency’ in Ireland. World War II raged in Europe and Ireland had adopted a stance of neutrality. At this time Ireland was still a relatively new independent State with no means of defence and Irish society was heavily influenced by the Roman Catholic Church. It was a time when crime and sin were deeply intertwined.

The article also describes the formation of the Irish Police Force: An Garda Síochána, and highlights how this police force was comprised of physically large young men. The majority from agricultural backgrounds, who had low levels of educational attainment and were predominantly Catholic. Darcy argues that at this time, the Gardaí were not only agents of the state, enforcing its laws, but they were also moral watchdogs, enforcing a version of social order that was in keeping with the religious teachings of the Roman Catholic Church.

The article presents both quantitative and qualitative data. The quantitative findings include tables detailing the type and number of crimes committed in these small villages between 1941 and 1943 and details relating to ‘culprits’ and ‘injured persons’. Interestingly, 31 out of the 83 culprits (37%) for the period under examination were children under the age of 18 years.

The qualitative aspect of the article examines four categories of crimes: concealment of birth; larceny; attempted suicide; and, indecent assault. The article also examines and discusses the authors of the volume: the Gardaí. Focusing in particular on their investigating and interrogation practices.

The contribution of the article lies in how it provides a vignette into rural crime and of the lives of those living in these small rural villages in Ireland during the 1940s. Darcy argues that crime and sin were deeply interwoven at this time and that morality featured heavily in the policing habitus of the Gardaí.

Much of the crime featured in the volume related to poverty and the austerity of social life during a national state of emergency. This article might appeal to those interested in historical rural crime, morality and crime, Irish policing history.

Pumping Iron in the Countryside: The Challenges of IPED Use in Rural Areas

Written by Dr Kyle Mulrooney

The use of image and performance enhancing drugs (IPEDs) is a growing issue, with users seeking to enhance their physical appearance and athletic performance. While much research has been done on IPED use, little attention has been paid to how rurality shapes IPED use and access to harm reduction services. This is a critical gap, as rural populations face unique challenges in accessing health services, and their experiences may differ from those living in urban areas.

The use of image and performance enhancing drugs (IPEDs) is a growing issue, with users seeking to enhance their physical appearance and athletic performance. While much research has been done on IPED use, little attention has been paid to how rurality shapes IPED use and access to harm reduction services. This is a critical gap, as rural populations face unique challenges in accessing health services, and their experiences may differ from those living in urban areas.

Dr. Luke Turnock and Dr. Kyle Mulrooney recently published an article in the journal Contemporary Drug Problems titled Exploring the Impacts of Rurality on Service Access and Harm Among Image and Performance Enhancing Drug (IPED) Users in a Remote English Region. The article is open access if you would like to read it in its entirety.

The study, conducted in a rural region of the United Kingdom, aimed to explore the barriers to accessing harm reduction services among steroid users. The research highlights the challenges faced by steroid users living in remote and often deprived areas. Specifically, the study found that while transport limitations and physical access to specialist services were highlighted as issues by participants, this was generally identified as an exacerbating factor on top of more significant barriers, surrounding perceptions of stigma and distrust of healthcare providers.

Steroid users in rural areas faced greater concerns over the personal impacts of being identified as a user on employment prospects. Additionally, the impact of small-town surveillance and stigma exacerbated the issue. As such, one key finding was the importance of anonymity to steroid users. Rural gym users, in particular, expressed the need to access injecting equipment and advice without being identified by neighbours and friends, which is made difficult by small-town contexts. There was also a need to seek health advice and monitoring without risking this being permanently recorded on medical records, in a way that could harm future employment prospects.

Steroid users in rural areas faced greater concerns over the personal impacts of being identified as a user on employment prospects. Additionally, the impact of small-town surveillance and stigma exacerbated the issue. As such, one key finding was the importance of anonymity to steroid users. Rural gym users, in particular, expressed the need to access injecting equipment and advice without being identified by neighbours and friends, which is made difficult by small-town contexts. There was also a need to seek health advice and monitoring without risking this being permanently recorded on medical records, in a way that could harm future employment prospects.

Connected to this, the study found that economic deprivation and class played a significant role in access to harm reduction services, with those perceiving they had few career prospects outside of the military being especially vulnerable. Particularly in regions where physical labour such as quarrying, agriculture, or the military are the primary avenues for good employment prospects among working-class men, understanding how IPED use may intersect with the strains of demanding physical labour is significant in directing harm reduction.

The impact of masculinities was also highlighted in the study, indicating that cultural conceptions of masculinity must be considered in discussing steroid use and harm, even when focusing on service access. Work to address issues in harm reduction access must consider not only perceptions of stigma among steroid users but also appropriate messaging to navigate self-stigma surrounding healthcare access among rural men.

The impact of masculinities was also highlighted in the study, indicating that cultural conceptions of masculinity must be considered in discussing steroid use and harm, even when focusing on service access. Work to address issues in harm reduction access must consider not only perceptions of stigma among steroid users but also appropriate messaging to navigate self-stigma surrounding healthcare access among rural men.

In conclusion, the study underscores the importance of understanding the challenges faced by steroid users in rural communities. Steroid use is a growing concern, and it is vital that policymakers and healthcare providers recognise the unique barriers faced by this population. By doing so, we can develop programs that meet the needs of steroid users and increase their engagement with harm reduction services.

Images in this blog post

The first image in this post, of the man riasing barbells, was created by the author using the AI software Dall-E using the promnpt “farmer lifting weights in paddock in a realist style”. The other images in this post are from pexels.com

Rural determinants of female prisoner reentry

This is the sixth and final post in a series of short topic snapshots, prepared by Joseph Loades, a research student with the Centre for Rural Criminology at the University of New England.

Female prisoners that are re-entering rural society after their period of incarceration face multiple problems. Other than the common issues that are encountered by males and females, such as lack of recovery services, public transport infrastructure, and access to internet (which can help with accessing employment and attending telehealth services), in rural and remote communities, females face many issues that are gender specific.

In an assessment of female prisoner reentry, Willging et al. (2016) state:

When compared to both rural men and urban residents, rural women face greater disparities associated with mental distress, substance use, and crime. They have less formal education, fewer employment options, and more poverty … These health and social inequities lead rural women released from prison to rely upon informal and insecure networks of family and friends to support them during and after their release. (para. 2).

Not only do women’s experiences of reintegration effect their own wellbeing, many of those that are re-entering society have children, broadening the effect of incarceration onto their offspring. Mothers that have full custody of their children are faced with further disparities.

Not only do women’s experiences of reintegration effect their own wellbeing, many of those that are re-entering society have children, broadening the effect of incarceration onto their offspring. Mothers that have full custody of their children are faced with further disparities.

In a study by Beichner and Rabe-Hemp (2014) it was found that women that were ‘sole-parents’ to their children generally take up that role upon release, and women that were disconnected from their children throughout their incarceration faced relationship vulnerabilities – such as intimate partner violence, addiction, and unstable familial relationships in every aspect of their lives – upon reentry.

These relational vulnerabilities manifest themselves through past trauma – such as intimate partner violence and childhood sexual abuse – which is more common in rural and remote areas – and behavioural and health interventions are generally lacking compared to metropolitan areas.

However, Beichner and Rabe-Hemp (2014) found that those that were participants of ‘family programming’ whilst incarcerated – which included continued contact with their children whilst in prison – did not experience relational vulnerabilities due to estrangement upon release. The application of ‘family programming’ in prison shows a strong protective factor.

Health and behavioural services are a valuable resource that address the issues faced by female prisoners upon reentry. But these services are far less common in rural and remote Australia, compared to metropolitan areas. Staton et al. (2019) explain the possible protective factors that influence successful female transition from prison to rural communities. The study found that drug use abstinence, health care utilization, and pro-social peers were the strongest protective factors.

Health and behavioural services are a valuable resource that address the issues faced by female prisoners upon reentry. But these services are far less common in rural and remote Australia, compared to metropolitan areas. Staton et al. (2019) explain the possible protective factors that influence successful female transition from prison to rural communities. The study found that drug use abstinence, health care utilization, and pro-social peers were the strongest protective factors.

Interestingly, the application of substance-use treatments did not play a major role in abstinence, and health care utilization was more beneficial. It was found that women that had a regular source of health care were 62% more likely to stay out of custody. The final protective factor, pro-social peers, can serve as a barrier against future offending and drug use. The study explained that an assessment of social support and social networks is useful in addressing the issue of anti-social peer association upon reentry.

(Images sourced from pixels.com).

References

Beichner, D. & Rabe-Hemp, C. (2014). “I don’t want to go back to that town:” Incarcerated mothers and their return home to rural communities. Critical Criminology, 22(4), 527-543. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10612-014-9253-4

Staton, M., Dickson, M. F., Tillson, M., Webster, J. M. & Leukefeld, C. (2019). Staying out: Reentry protective factors among rural women offenders. Women & criminal justice, 29(6), 368-384. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08974454.2019.1613284

Willging, C. E., Nicdao, E. G., Trott, E. M. & Kellett, N. C. (2016). Structural inequality and social support for women prisoners released to rural communities. Women & Criminal Justice, 26(2), 145-164. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4889023/